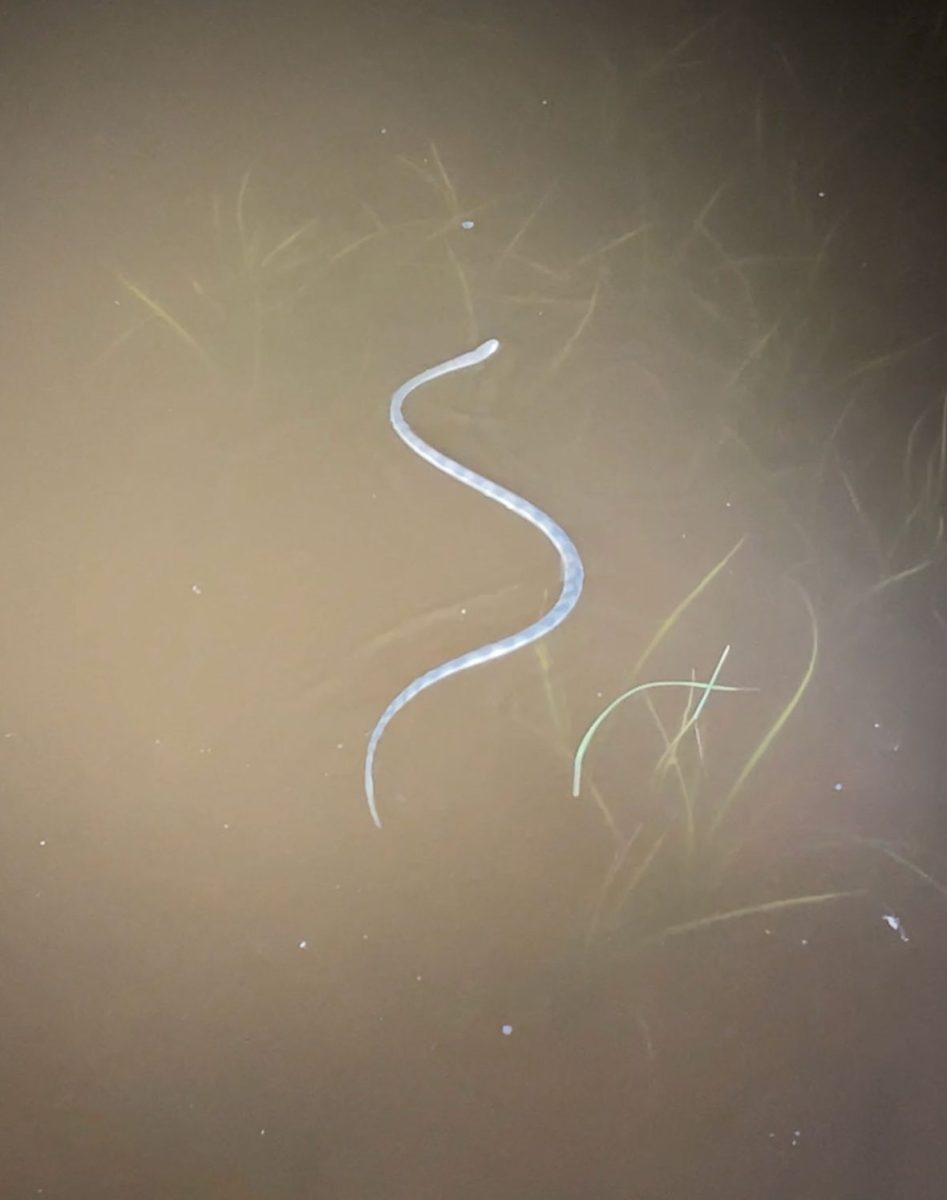

Ethan Maguire and Rhys Barrot were walking along a rough dock road in Borneo beside brackish water, where salt and freshwater mixed and the jungle pressed in. It was a quiet place and, turning to their right, they saw what looked at first like just another water snake. It was a quick find on a long list of finds, and nothing they hadn’t handled already. Rhys, under the impression that he’d spotted another harmless puff-faced water snake, reached down into the water and picked it up. It seemed like a throwaway moment, a quick photo opportunity and dopamine hit before getting back to looking for other, more dangerous species.

Yogi, their friend and local guide, was better versed, and wary of mistaking an escalating emergency for harmless fun. His eyes darted immediately to the tail of the snake, which tapered at the end to form a paddle. He was the first to realise that this wasn’t a water snake, but a sea snake.

On the outside, sea snakes don’t appear an immediate threat. It can be easy to mistake them for their freshwater counterparts, which are generally non-venomous and, aside from the bite itself, harmless to humans. In comparison, sea snakes are highly venomous, possessing potent neurotoxins to paralyse fish. Some species’ venom is more toxic than most land snakes, and between four to eight times more than that of a cobra. The average sea snake is generally docile but dangerous if threatened, and does not like being handled. But the species Rhys had spotted was a beaked sea snake, which sounds elegant but is far from it. This species is often described as “cantankerous”, prone to biting and extremely venomous. They are responsible for around 90% of sea snake fatalities.

Unaware of the danger at the time, Rhys examined the snake and, in the split second that it recoiled to bite him, threw it back in the water. The fangs missed him by about two centimetres. If his reflexes hadn’t kicked in, he almost certainly would have died. “I don’t know what we would have done if he was bitten,” Ethan reflected, now outside of the situation. Whilst countries such as Australia have species-specific antivenom for sea snakes, it’s generally not available within Indonesia’s healthcare system. Imported antivenom for specialised bites like sea snakes often requires sourcing it from Australia or Thailand, which can cost thousands. But with symptoms from a bite beginning within five minutes, and fatalities possible in under thirty, this wouldn’t have been much use as a back-up.

This narrow miss is the type of story you expect to hear from outback Australians or hosts of wildlife documentary series, not sitting outside CafeJAC over an Americano on a Tuesday afternoon. For Ethan and Rhys, it was the everyday predictability of living on a relatively safe island that they wanted to escape. They’d previously been away together and experienced the thrill of living in the present, finding purpose in hunting wildlife and gaining satisfaction from surviving danger and living to tell the tale. In spaces like these, it was easier for them to simplify life by adopting a survivalist mindset and interacting with species that thrive in foreign climates.

The way the trip began was the opposite of meticulous planning. “Honestly, we planned it so spontaneously,” Ethan laughed. “We went to the pub for a random drink in the middle of the week and just thought, ‘what’s stopping us from going into the jungle again?’” Life in Jersey was nice, the boys agreed, but comfort had started to feel like a slow leak, and they missed the exhilaration of being in wildlife and feeling alive. Indonesia was the most practical option. It’s cheap to live in and one of the best places to see a variety of wildlife. They set a date to leave and, aside from booking flights, began planning the day prior to leaving. Even then, the “plan” was to book one night in a hostel in Sulawesi and roll with where the road took them. The lack of planning became integral to the story’s shape, later allowing them to venture into Borneo.

~

On arrival in Sulawesi, the boys were intent on tracking down a species of snake they knew lived in the area. Tangkoko National Park, located in the north of the region, is a 9000-hectare biodiversity hotspot famed for hosting unique, endangered wildlife. Amongst observing these rare species, their main goal was to find and hold a reticulated python. These snakes, whilst not endangered, make their home in the rainforests of Tangkoko and are expert camouflagers in leaf litter. They are the longest species of snake in the world, regularly exceeding six metres in length, with historical records of individuals reaching over nine. While non-venomous, they are constrictors that kill through suffocation, and their size and sharp, backward-curved teeth make them dangerous to humans, which they have been known to swallow whole. Their only predators are crocodiles, king cobras and humans.

Ethan spoke about these snakes with the casual air of someone narrating current affairs at the dinner table, adding that “in the news each year you see at least one or two people in Sulawesi who have been eaten by a reticulated python.” Heru, one of their friends, once went viral for diving into waters infested with saltwater crocodiles to emerge pulling out a five metre reticulated python from the river with his bare hands. He became known as the eagle eyes of the group and is not averse to danger. When he found an injured baby saltwater crocodile in local waters, he rescued it and brought it home as a pet. These crocodiles are feared in Indonesia, killing approximately 85 to 100 people annually, the highest rate globally. In comparison, reticulated pythons are child’s play.

But these snakes can be hard to find. In addition to their camouflage skills, they often hide beneath the water and can hold their breath for thirty minutes at a time. They coil around tree branches out of reach and only venture onto land during the dark hours. It was at this time that Ethan and Rhys found a young member of the species. Whilst not the six to seven metre variety that wrought stories amongst villagers, this freshly hatched reticulated python was beautiful, already patterned, and brought a fresh sense of positivity to the night. Rhys held it loosely while Ethan documented it. “It was good news,” explained Ethan, “because it meant that a mother must also have been nearby, having laid her eggs not too long ago. A lot of people think if you pick up a snake the first thing they’re going to do is bite you, but as long as you’re handling them correctly, it’s generally okay.” They let the baby go and, after an unsuccessful search for the mother, accepted that they were going to be unlucky in Tangkoko. They hadn’t found their monster yet.

~

After leaving Sulawesi, they flew from Manado down to Jakarta and then up to Pangkalan Bun in Borneo. It arrived with mud, heat and a fresh set of animals. There, they met up with a group of friends they’d met online earlier in the trip, who operated an informal wildlife network through the fire station, receiving calls about rogue snakes, rescuing them and returning them to the wild. The fire service acted as a catch-all emergency unit for community safety and animal rescue. “The fire service does everything over there,” he explained. “Some of the team are trained in rescuing snakes.”

One day, they went with them, starting with smaller rescues such as rat and vine snakes. The former, whilst not venomous, were prone to biting and left marks on the pair. The latter are delicate and surreal-looking, with thin, pointy mouths and venom that Ethan dismissed as “about the same as a bee sting.” In the end, this snake was not returned to the wild; Heru gave it to his kids, to keep as a pet.

Despite not yet finding the reticulated python they were searching for, Ethan and Rhys came face to face with one of its only predators, the king cobra. The fire station received a call that one had ended up in someone’s house and had gone out to rescue it, bringing it back to the station. It was Ethan and Rhys’ task to release it.

Ethan reflected on the absurdity of it all and how strange it sounds to say out loud back in Jersey. King cobras are animals we associate with documentaries and warnings, and suddenly Rhys is on the back of a moped with one inside a tied bag resting on his lap. Ethan is also on the back of a moped, balancing a box of other snakes. Their friends Yogi and Hengky, who are driving, act like nothing is outside the norm. This is especially weighted, because Heru is with them, and his story is cast with the shadow of grief due to one of these snakes.

“They lost their… one of their best friends,” Ethan explained. “It was Heru’s best mate. A king cobra bit him a few months ago, and he passed away.”

“We got this feeling that there was a different energy in the air when we opened up this bag, with these boys,” he added. “For Heru, when it comes to king cobras, he’s always really careful around them. Because one bite, and that’s probably it.”

It was after this moment of rescue and release, with the cobra back in the wild, that the night brought the boys the other thing they had been chasing. For Ethan especially, this was all that he’d been waiting for. Walking at night along the riverbed, they stumbled across a reticulated python. In the video he documented, he secures the snake with a firm grip behind the head, showing a close up view of its backward-curved teeth, two rows on the upper and lower jaws and another row lining the middle of the mouth. These fangs have the power to rip through arteries when a person instinctively pulls away after being bitten. Coiled around his arm, the weight made him out of breath. “If you don’t grab the python right behind its head, it’s going to wrap around and bite your hand, then you’re screwed,” he explained. This part of the body is particularly vulnerable, due to the concentration of major blood vessels in the area. The python went for Ethan’s leg and, in a last minute manoeuvre, he managed to control it before it connected. He emerged unscathed with a feeling of euphoria. “I was so stoked to find one,” he exclaimed. “Even if it was only about two or three metres.”

~

The rest of their trip repeated with the same motions. They spent nights herping for reptiles or walking through tall grass searching for species such as Malayan pit vipers. These are small brown snakes that even Ethan admitted “you really don’t want to get bitten by.” The logic of survival is to carry a torch and hope you don’t step on one. When handling them, it’s best to use a metal hook, as heat-sensing pit vipers are likely to attack your hand thinking it’s food.

Then there were the mangroves, both the habitat and the snakes that share its name, and the mild insanity of moving through crocodile water like it’s a normal step in the process. “You never really see them,” Ethan said reassuringly, adopting an out of sight, out of mind mindset. In the daytime, the black-and-yellow mangrove snake sleeps in trees and, after spotting one, Ethan climbed up to get it. The snake spooked, fell into the saltwater crocodile infested water, and Heru jumped in to fish it out. The first time, they lost it, but after committing a second time, they retrieved it. Ethan instinctively jumped into the water with Heru, and the pair emerged holding either end of the snake. “I don’t really know what I was thinking in that moment,” Ethan laughed. “But if we didn’t jump in we wouldn’t have found it.”

The trip kept looping through euphoria, danger and relief, and by the end it came back towards the animal even the boys didn’t want to mess with. In the final days, Diaz had another king cobra rescued from a nearby village. It had a scar on its face from being attacked and Diaz was nursing it back to health before releasing it.

“This was my first time interacting with the king cobra myself,” Ethan explained. His aim was to get close, observing how it worked and figuring out its personality. “When you get close to the king cobra, it’s very beautiful. They’re really colourful.”

This king cobra wasn’t shy and made its aggressive personality clear. Ethan wanted to experience the challenge of trying to kiss it on the back of the head. This was a deliberate experiment to test the cobra’s attention prior to releasing it back into the wild. King cobras get into a hypnotic state when they are looking at the person in front of them because they are completely sight orientated. In this case, it didn’t even have to be a person. “Diaz was taking a video, and my phone became a sort of target for the king cobra,” he explained. “We saw it going into a hypnotic state.”

“My heart was pumping,” he recalled. “I remember thinking it was a bit crazy.” Testing the boundaries, he touched the back of its head and the cobra’s attention remained focused on the phone. As he leaned closer, the orchestration nearly collapsed. “It just snapped out of it,” Ethan said. “That’s the first time my heart has dropped. If it’s lost focus, that means it’s felt my presence. If it sees my hand, now my hand becomes a target. If I move my hand backwards, he’ll still identify it as a target and launch.”

Trying not to create the one thing the cobra would react to, Ethan held still. “I tried to calm myself down, not make any sudden movements. If things went wrong in half an hour I could just be dead,” he said.

At this point, everything rested on whether Diaz could re-catch its gaze. Ethan noticed the exact moment the king cobra locked back in, leaned down the rest of the way and kissed it.

“I got a cool photo of me doing it,” Ethan said. Then he returned to the facts that sit beneath his fascination. “Apparently, it can kill twenty adult humans,” he asserted. “Or otherwise, a fully grown African elephant.”

~

Of all animals to fall in love with, snakes are one of the more rogue species. Ethan admits he doesn’t understand the obsession himself. “People always ask me why I like snakes and reptiles so much, and I have to tell them I honestly have no idea,” he said. “My best explanation is that I was born in South Africa and my cousin Luke loved snakes, so we’d always go out looking for them together.” He moved away young, at only six years old, and admitted that his memories of Johannesburg are blurry. But the more clear-cut fragments of his early childhood tend to be characterised by the presence of animals. Mostly scaly ones, with a good set of fangs.