Photography: Laura Dos Ramos

In a world exhausted by digital, ‘analogue’ has become the most ‘authentic’ trend. Instagram grids have become filled with vintage, hazy photographs, deliberately edited to feel like they were from an age where images were printed and pasted into dated, stacked albums. Analogue has a feeling of tangibility that we instinctively miss when the majority of our information is handed to us through a handheld screen, regardless of whether we’d actually feel the same if we were carting heavy magazines and books slung over our shoulder. As with most things, the impracticalities of the past rarely bear weight when reminiscing nostalgically on a world that has come to pass.

Alongside this romanticisation of the old, and disillusionment with the new, more and more photographers have been stepping into film as their medium of choice. Despite modern digital imaging being capable of capturing each individual pore in a portrait, the rusty, grainy and discoloured frames produced by film have captured the attention of those who’ve tired of RGB. Even the method of taking these photos carries a sense of importance and consequence not shared with digital – a sentiment expressed by Laura Dos Ramos, a Jersey-born photographer currently living in London. “Film photography has always been central to my practice,” she writes. “I admire it for its limited number of frames, encouraging a slower, more thoughtful approach. Each image feels intentional.”

The approach demanded by this medium was a perfect fit for her latest project, No Place Like Home, which captures the realities of living in staff housing in Jersey, inspired by her own experience growing up in these environments. Through long conversations and sensitive documentation, she created an expansive body of work that aimed to explore what brings a sense of ‘home’ in a place that can, at times, feel fundamentally liminal; whether that be between work and rest, or in the act of setting down roots in a borrowed space. Below she reflects on how the experience reshaped her understanding of her own upbringing, whilst sharing the stories of the people within each set of four walls.

“No Place Like Home was a project that came together bit by bit. In my final year of university, we were handed the task of creating a long-term body of work based on an idea that could be explored, developed and expanded throughout the year, before eventually being showcased at a graduate exhibition in London. It prompted me to think about issues that felt both significant and unsolved. Although I was raised in staff housing, I didn’t actively question it for a long time because it seemed normal. I didn’t realise how much these places had influenced my perception of home, and how unique that upbringing might be, until I moved away from Jersey to attend university.

No Place Like Home was born out of that realisation. What started as an honest effort to better understand my own upbringing, shaped by my parents and the staff houses they lived in long before I was born, grew into conversations with current and former residents of other staff houses. Since then, the body of work has developed into an exploration of staff housing as a common, but mostly unseen, experience shaped by the lives that move through these places.

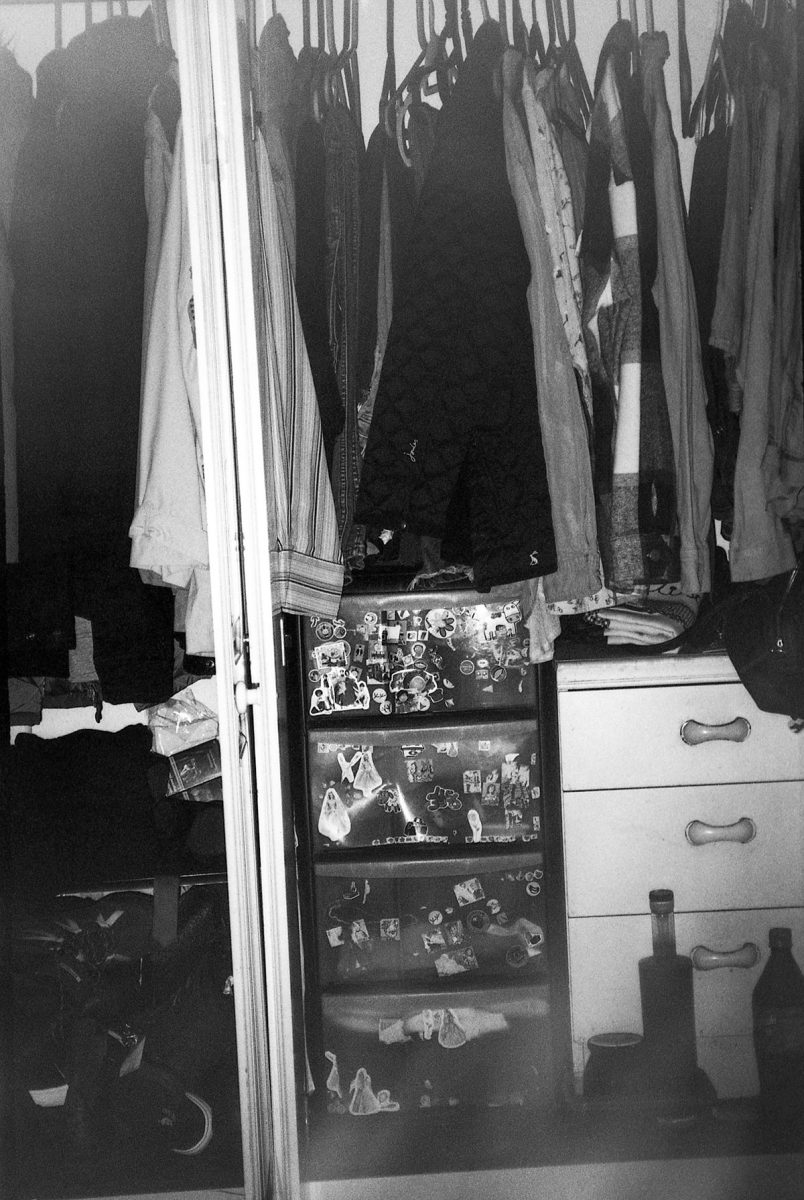

Growing up in staff housing gave me a complicated view of stability and belonging, which influenced how I observed home. A roof over my head, loving parents, and a feeling of family and community felt like security. Watching people move through these areas as a child shaped my perception of connection and the relationships that form in shared environments.

However, there was also an awareness that the space wasn’t fully ours. This felt normal to me as a child, but it gave me the impression that belonging might not always be guaranteed. Home was familiar and reassuring, but also fragile and fleeting, something valued even though one knew it might change.

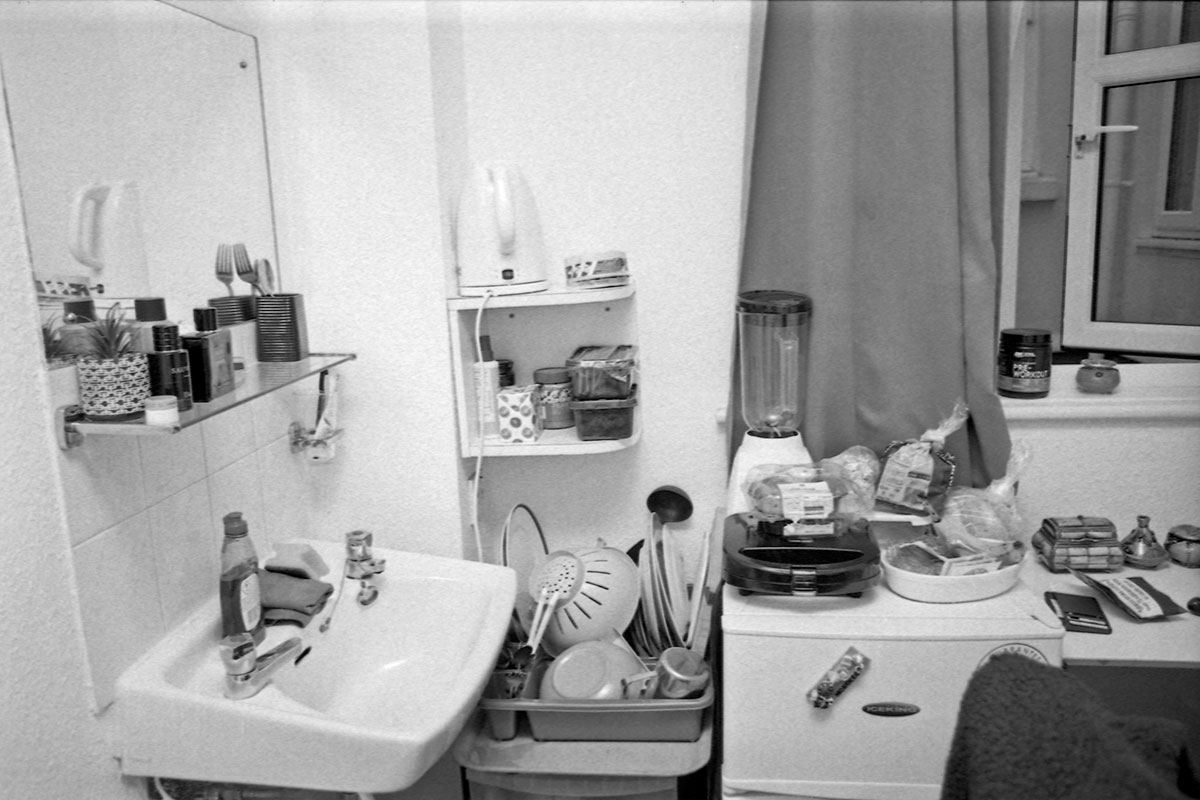

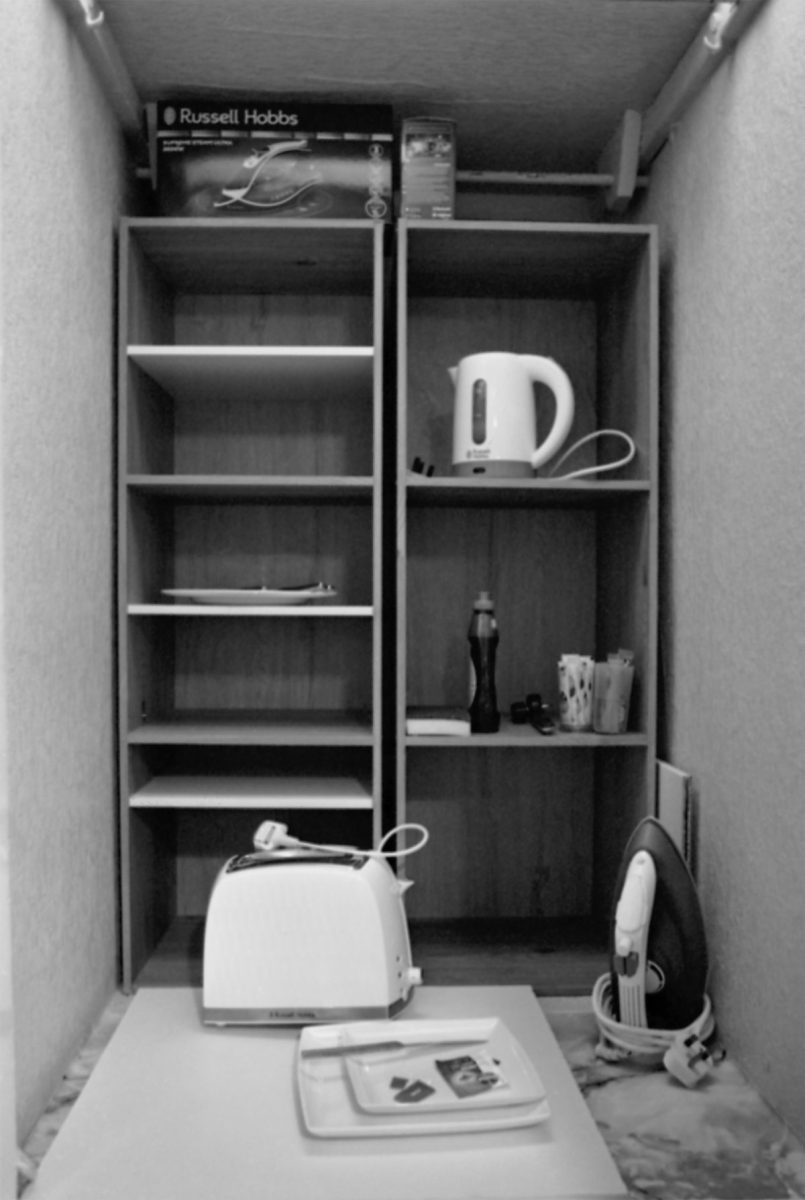

As I photographed different staff houses, the biggest pattern that stood out was the lack of structure. Staff housing is rarely the same: you’re usually just given a room, and everything else is organised by management. Sometimes your room is your own, other times you’re sharing. It’s often split by gender, and in some cases, there can be several people in one room.

These places can be inside the workplace, in separate buildings, or nearby. They tend to be practical rather than personal, covering the basics but rarely feeling like somewhere you’d properly call home. Whether it feels like a liminal space between work and home depends on the building and the people living there. Some of the places I photographed used to be completely different things, like family-run restaurants or bed and breakfasts, and still hold onto that original feel. Others have been adapted specifically for staff accommodation. Either way, there’s often a sense of time passing, as if the past of the building is still present.

Living with coworkers also makes it harder to draw a clear line between work and personal life. The spaces feel lived-in, but never permanent. Daily routines, privacy and social life are tied back to the job. There’s comfort and familiarity, but you’re always aware that it’s temporary; that ‘home’ can shift depending on work and could change suddenly.

Beyond the physical spaces, what stood out was the mix of people living there. Everyone has their own reason for being in staff accommodation, coming from different backgrounds, ages and cultures. For some, it’s a short-term solution while they earn money; for others, it’s a way to support family elsewhere. These places are communal, yet deeply personal at the same time.

When your job and accommodation are never fully separate, there are power dynamics at play. Where and how you live often depends on your role, your employer and how closely you’re expected to follow the rules. Everyone’s experience of staff housing is different, and conditions vary depending on the industry or how the place is managed. Even when it’s not obvious, these dynamics quietly shape everyday life within these spaces.

One of the most important parts of the project was access and consent. I always spoke to the residents first, explained what the project was about, and made sure they were comfortable being involved. Everyone had the option to say no or change their mind at any point.

I also set my own boundaries. Instead of photographing anything too personal or intrusive, I focused on the spaces themselves. The surroundings, everyday objects and overall atmosphere were the most important aspects of reflecting how people live there day to day. Because of these conversations and the care I took, the project became collaborative. The residents’ willingness to share their homes made it possible to capture both the spaces and the stories within them.

Despite being a crucial aspect of life for many employees, staff housing is often overlooked and rarely discussed. These spaces are practical and private, and the people living in them often remain invisible to the wider community. This project aims to make those spaces and lives more visible. Photographing staff accommodation highlights the range of people who live there, from different ages and backgrounds, and shows how the layouts, rules and working conditions shape everyday life. Ultimately, the project suggests that staff housing is more than just a place to sleep; it’s an environment that reflects both the demands of work and the experiences of those who share it, even temporarily.

This is an ongoing body of work, and so far, I am extremely grateful to everyone who has shared their experiences with me, allowing me to expand the concept. I want to continue pursuing this subject by speaking with more residents and documenting more places.

What began as my own perception of home grew through conversations with residents, revealing a range of experiences shaped by work, circumstance and temporary living conditions. The project intends to shed light on these stories and explore how ideas of home and belonging exist even in changing circumstances.

My objective is to acknowledge these experiences and make room for lives that are often overlooked, rather than to speak for others. As the project unfolds, I hope the photographs and words encourage people to take a closer look and consider what home might mean.”